Have you ever enjoyed a piece of black licorice candy, sipped on licorice tea, or taken a herbal supplement labeled "licorice root" while on blood pressure medication? If so, you might be putting your health at risk - and you’re not alone. Many people don’t realize that something as simple as licorice can interfere with their prescription drugs, making them less effective or even dangerous. This isn’t a myth or an old wives’ tale. It’s a well-documented, clinically proven interaction that can lead to high blood pressure, low potassium, heart rhythm problems, and even hospitalization.

How Licorice Actually Raises Blood Pressure

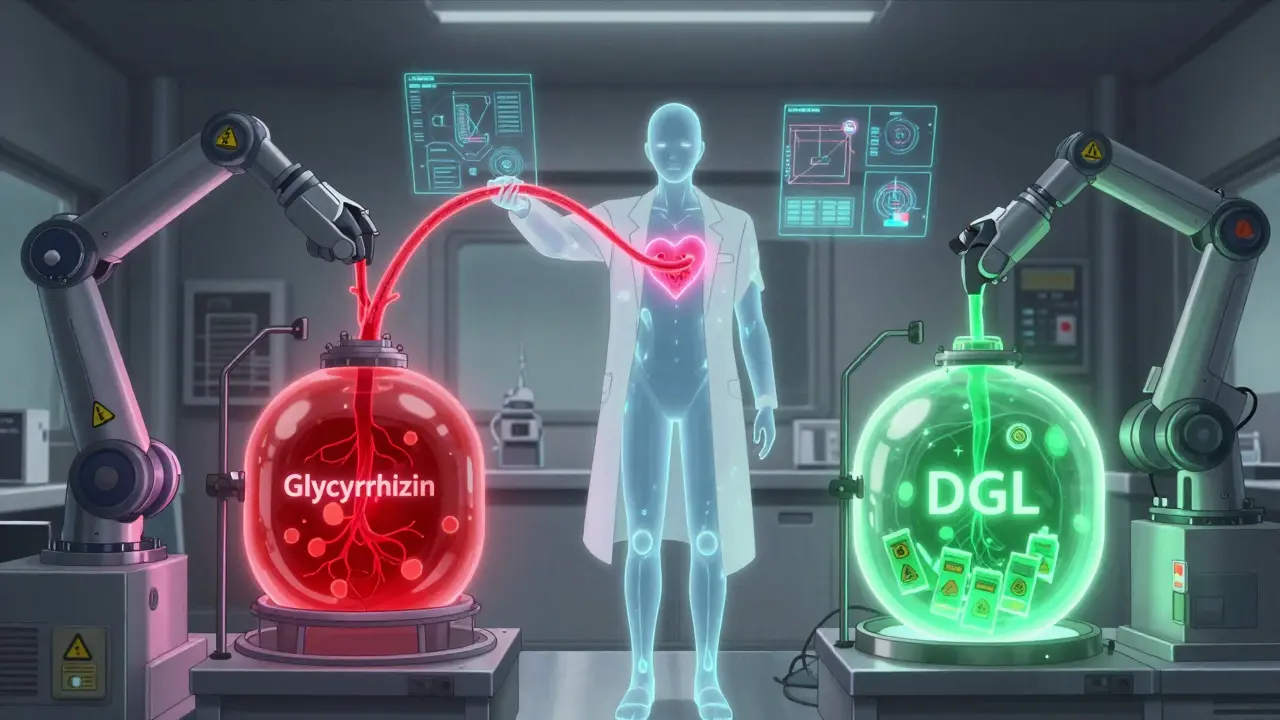

Licorice root contains a compound called glycyrrhizin, which your body breaks down into glycyrrhetic acid. This acid blocks an enzyme in your kidneys called 11β-HSD2. Normally, this enzyme protects your body from cortisol - a stress hormone that acts like aldosterone, a hormone that makes your body hold onto salt and water and flush out potassium. When 11β-HSD2 is blocked, cortisol takes over and mimics aldosterone. The result? Your body holds onto extra fluid, your blood volume increases, and your blood pressure goes up.

This isn’t just a minor bump in numbers. Studies show that consuming more than 100 mg of glycyrrhizin per day can raise systolic blood pressure by an average of 5.45 mmHg and diastolic by 1.74-3.19 mmHg. For someone already struggling to control their hypertension, that’s enough to undo weeks of medication progress. And it doesn’t take much: 60-70 grams of traditional black licorice candy - about two to three standard packs - contains roughly 100 mg of glycyrrhizin. That’s less than you might think.

Why This Matters With Blood Pressure Medications

Most blood pressure medications work by helping your body get rid of excess fluid or relax your blood vessels. But licorice does the opposite. It makes your body hold onto fluid, which directly counters what your meds are trying to do.

- Diuretics like hydrochlorothiazide or furosemide help you pee out extra salt and water. Licorice makes you hold onto salt and water - so your diuretic becomes less effective.

- ACE inhibitors like lisinopril or captopril lower blood pressure by relaxing blood vessels and reducing fluid retention. Licorice floods your system with fluid, making these drugs struggle to keep up.

- Potassium-sparing drugs like spironolactone or eplerenone are designed to keep potassium levels up. But licorice flushes potassium out of your body - so you’re fighting a losing battle.

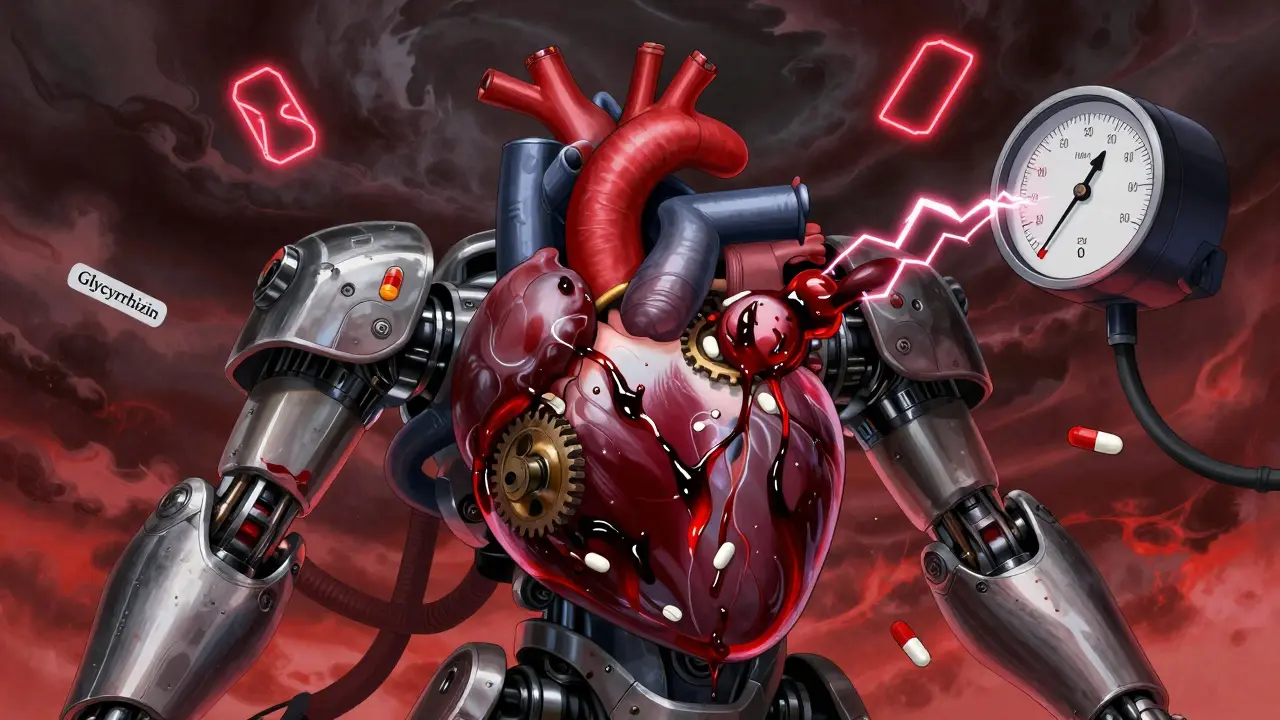

Worse still, licorice can make your potassium levels drop dangerously low - often by 0.5 to 1.0 mmol/L after just two to four weeks of regular use. Low potassium doesn’t just cause muscle cramps or fatigue. It can trigger irregular heartbeats, muscle weakness, and in severe cases, paralysis or cardiac arrest.

The Most Dangerous Combo: Licorice and Digoxin

If you’re taking digoxin (Lanoxin) - a common heart medication used for atrial fibrillation or heart failure - licorice becomes a ticking time bomb. Digoxin works by slowing your heart rate and strengthening contractions. But it needs a certain level of potassium to be safe. When potassium drops too low, digoxin binds too tightly to heart cells, causing toxicity.

There’s a documented case from a patient who developed congestive heart failure after taking a herbal laxative that contained licorice. He wasn’t even aware it was there. His potassium plummeted, his digoxin levels spiked, and he ended up in the hospital. This isn’t rare. It’s predictable. And it’s preventable.

Who’s at Highest Risk?

Not everyone reacts the same way. Some people can eat a small amount of licorice without issue. Others - especially those with existing health conditions - are far more sensitive.

- People over 60 - your kidneys don’t clear glycyrrhizin as efficiently.

- Women - studies show higher sensitivity, possibly due to hormonal differences.

- Those with existing high blood pressure - even small fluid shifts can push you out of control.

- People with heart disease or kidney problems - your body is already under stress.

Even if you’re not on medication, if you have high blood pressure, you should avoid licorice. The Merck Manual and MSD Manual both say it clearly: people with hypertension must not consume licorice root.

What Counts as Licorice? (And What Doesn’t)

Not all licorice-flavored products are the same. In the U.S. and many other countries, red licorice - the chewy, fruity kind - is usually flavored with anise or artificial flavors and contains no actual licorice root. But black licorice? That’s the dangerous kind. It’s often made with real licorice extract.

Also watch out for:

- Licorice tea - especially herbal blends marketed for digestion or "detox."

- Dietary supplements - many contain licorice root for "adrenal support" or "anti-inflammatory" claims, with no clear labeling of glycyrrhizin content.

- Traditional medicines - licorice is common in Chinese herbal formulas, Ayurvedic remedies, and European herbal preparations.

Check the label. If it says "licorice root," "Glycyrrhiza glabra," or "glycyrrhizin," assume it’s active and potentially harmful. If it just says "natural flavoring," it’s probably safe - but don’t assume. When in doubt, avoid it.

What to Do If You’ve Been Eating Licorice

If you’ve been regularly eating black licorice or taking licorice supplements while on blood pressure meds, here’s what to do:

- Stop immediately. Even if you feel fine, the damage can be silent.

- Get your potassium checked. A simple blood test can show if your levels are low (below 3.5 mmol/L).

- Monitor your blood pressure. Take readings at home for a few days. If your numbers have climbed by 5 mmHg or more, contact your doctor.

- Look for symptoms: Muscle weakness, fatigue, heart palpitations, swelling in your ankles, or unexplained headaches could be signs of licorice toxicity.

Your doctor may order a cortisol-to-cortisone ratio test - a specialized blood test that confirms licorice’s effect on your enzyme system. If levels are abnormal, they’ll likely advise you to avoid licorice completely.

What About Deglycyrrhizinated Licorice (DGL)?

You might have heard of DGL - a form of licorice where glycyrrhizin has been removed. This version is often sold for stomach ulcers or acid reflux. Since it doesn’t contain the problematic compound, DGL doesn’t raise blood pressure or lower potassium. If you need licorice for digestive reasons, DGL is the only safe option - but make sure the product clearly says "deglycyrrhizinated" and doesn’t list glycyrrhizin on the label.

Final Advice: Be Proactive, Not Reactive

Doctors don’t always ask about herbal supplements or candy habits. You have to speak up. When you see your provider, say: "I eat licorice candy occasionally" or "I take a herbal tea with licorice root." Don’t assume it’s harmless. Don’t assume they’ll know. This interaction is well-known in medical literature - but it’s still overlooked in practice.

If you’re on blood pressure medication, treat licorice like alcohol or grapefruit juice: avoid it unless your doctor says otherwise. Your meds are working hard to keep you healthy. Don’t let a piece of candy undo that.

Can I eat licorice if I’m not on blood pressure medication?

If you’re healthy and don’t have high blood pressure, occasional small amounts (less than 100 mg glycyrrhizin per day) are unlikely to cause harm. But even then, regular use can still lead to low potassium, fluid retention, or elevated blood pressure over time. It’s safest to avoid daily consumption. If you have kidney disease, heart disease, or are pregnant, avoid it entirely.

How long does it take for licorice to affect blood pressure?

Effects can start within a few days, but clinically significant changes usually appear after 2-4 weeks of daily use. The longer you consume it, the more your body holds onto fluid and loses potassium. Stopping licorice can reverse the effects - but it may take several days to weeks for your blood pressure and potassium to return to normal.

Are there any safe licorice products?

Yes - deglycyrrhizinated licorice (DGL) is safe because the glycyrrhizin has been removed. Look for products that clearly state "DGL" on the label. Avoid anything labeled "licorice root," "glycyrrhizin," or "Glycyrrhiza glabra" unless you’ve confirmed it’s DGL. Red licorice candy (flavored with anise) is also generally safe, but check ingredients to be sure.

Can licorice affect other medications besides blood pressure drugs?

Yes. Licorice can reduce the effectiveness of warfarin (a blood thinner), increase side effects of corticosteroids, and interfere with certain chemotherapy drugs like paclitaxel and cisplatin. It can also interact with diuretics, heart medications, and even some antidepressants. Always tell your doctor or pharmacist about any herbal supplements you’re taking.

Why isn’t there a warning label on licorice candy?

In the U.S. and many countries, there are no federal requirements for licorice products to list glycyrrhizin content or include health warnings. Supplements are even less regulated. This lack of labeling creates hidden risks - people don’t know they’re consuming a potent drug-interacting compound. Some countries, like New Zealand (Medsafe), have issued warnings, but enforcement and consumer awareness remain low.

If you’re managing high blood pressure, your medication is only as good as your consistency - and that includes what you eat, drink, and take. Licorice isn’t just a sweet treat. It’s a physiological disruptor. For your heart’s sake, skip it.

Lydia H.

January 18, 2026 AT 01:28I used to love black licorice like it was candy therapy-until my grandma told me she stopped eating it after her BP spiked. Turns out she was right. Now I just chew anise-flavored red licorice and call it a day. No drama, no hospital visits. Sometimes the simplest swaps save your life.

Astha Jain

January 19, 2026 AT 22:44so like… licorice is basically a sneaky drug?? like wtf why is this not on the packaging?? i mean i thought it was just a flavor not a full on endocrine disruptor 😭

Lewis Yeaple

January 21, 2026 AT 12:46While the post accurately outlines the pharmacological mechanism of glycyrrhizin-induced pseudoaldosteronism, it fails to contextualize dose-response variability across populations. The 100 mg/day threshold is derived from controlled studies, yet real-world consumption patterns-particularly among elderly populations-are often sporadic and below this threshold. Furthermore, the conflation of all licorice-flavored products with glycyrrhizin-containing varieties is misleading and potentially harmful to consumer autonomy.

Regulatory agencies have not mandated labeling because the risk-benefit ratio does not meet the threshold for public health intervention in non-patient populations. This is not negligence-it is evidence-based policy.

Malikah Rajap

January 22, 2026 AT 09:24Okay, but… have you ever thought about how much we just… trust candy? Like, we eat it like it’s harmless, but it’s basically a silent saboteur? I mean, I had no idea licorice could mess with my potassium… and I thought I was being so healthy with my herbal teas. 😅

Also, I just checked my cupboard-there’s a bag of ‘licorice root tea’ I bought because it ‘helps with stress.’ I’m tossing it. I’m not dying because I wanted to feel zen.

And DGL? That’s the hero we didn’t know we needed. Why isn’t everyone talking about DGL??

Also, I told my mom. She’s 72. She’s been eating licorice since the 70s. She’s now terrified. And honestly? Good. We need more of this awareness.

sujit paul

January 24, 2026 AT 07:45This is not an accident. This is a system failure. Big Pharma doesn’t want you to know that a $2 candy bar can undo $500/month of medication. They profit from your dependency. Licorice is not the villain-corporate negligence is. Why isn’t the FDA forcing warning labels? Because they’re bought. Look at tobacco. Look at sugar. Look at this. It’s the same playbook.

And don’t get me started on Ayurvedic supplements imported from India-no regulation, no testing, just ‘ancient wisdom’ wrapped in cellophane. People are dying quietly while corporations count their coins.

Aman Kumar

January 25, 2026 AT 14:53Let’s be real: anyone who consumes licorice root while on antihypertensives is engaging in self-sabotage at a biochemical level. The glycyrrhizin-mediated inhibition of 11β-HSD2 is not a theoretical risk-it’s a quantifiable, dose-dependent, clinically reproducible phenomenon with documented case reports spanning decades. This isn’t folk medicine-it’s pharmacokinetic sabotage.

And the fact that people still consume it under the guise of ‘natural remedies’ reveals a deeper cultural pathology: the romanticization of herbalism without understanding molecular pharmacology. You don’t get to opt out of biochemistry because you ‘believe in nature.’

Jake Rudin

January 26, 2026 AT 10:36So… I’ve been eating licorice for years. I’m 45, no meds. But I’ve had weird muscle cramps lately. Could this be…? I mean, I didn’t think it mattered if I wasn’t on BP meds. But now I’m scared. I just stopped it. I’ll get tested tomorrow. Thanks for the wake-up call. I didn’t even know this was a thing.

Phil Hillson

January 27, 2026 AT 12:49Okay but like… is this even real? Like, I eat licorice every week and I’m fine. My BP is perfect. I think this is just fearmongering. People are scared of candy now? What’s next? warning labels on apples because they have sugar??

Josh Kenna

January 29, 2026 AT 02:38I just got off the phone with my cardiologist after reading this. I’ve been taking lisinopril for 3 years and I had no idea. I used to drink licorice tea every night to ‘soothe my throat.’ She said my potassium was low-like, dangerously low. I’m so mad I didn’t know. But also… thanks for posting this. I’m telling my whole family now. I’m deleting all my herbal tea apps.

Also-DGL? I’m ordering some for my acid reflux. I didn’t even know that existed. You’re a lifesaver.

Erwin Kodiat

January 31, 2026 AT 01:26As someone from the U.S. who grew up in a family that used licorice root in every cold remedy, this hit hard. My grandma swore by it. Now I’m realizing she might’ve been slowly poisoning herself. I’m going to make a little handout-‘Licorice: The Sweet Saboteur’-and hand it out at my mom’s senior group next week. Knowledge is power, but only if we share it.