Opioid Dosing Calculator for Liver Disease

How to Use This Tool

Enter your opioid type and liver condition severity to calculate:

- Adjusted dose percentage

- Extended half-life

- Risk level based on article data

Important: This tool provides general guidance only. Always consult your physician before adjusting medications.

When someone has liver disease, taking opioids isn't just riskier-it can be dangerous in ways most people don’t realize. The liver doesn’t just filter toxins; it’s the main factory that breaks down opioids. When it’s damaged, those drugs don’t clear the way they should. They build up. And that buildup doesn’t just mean longer pain relief-it means higher chances of overdose, confusion, breathing problems, and even death.

How the Liver Normally Processes Opioids

The liver uses two main systems to break down opioids: cytochrome P450 enzymes and glucuronidation. These are like specialized machines that chop up drugs into smaller pieces so the body can flush them out. Morphine, for example, gets turned into two main metabolites: morphine-6-glucuronide (M6G), which helps with pain, and morphine-3-glucuronide (M3G), which can cause seizures and nerve damage. In a healthy liver, these metabolites are made in balance and cleared quickly.

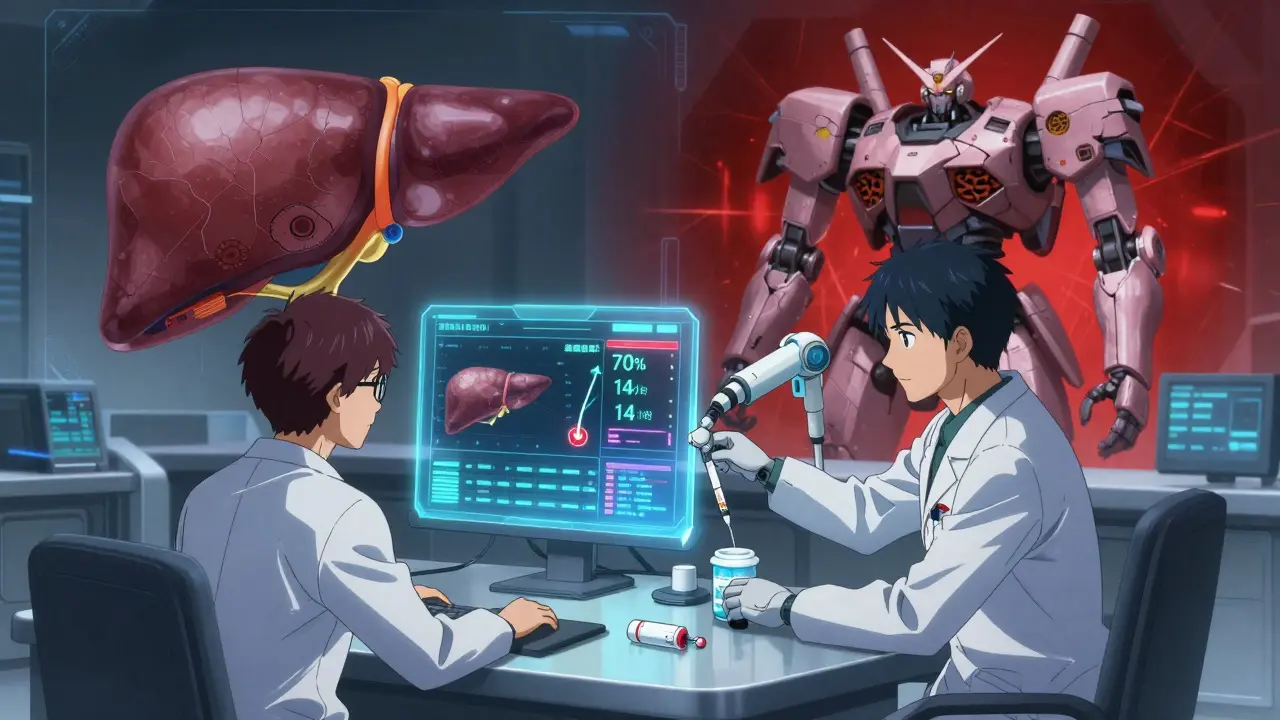

Oxycodone works differently. It’s broken down mainly by CYP3A4 and CYP2D6 enzymes. If those enzymes slow down, the drug stays in the blood longer. Normally, oxycodone clears in about 3.5 hours. In someone with advanced liver disease, that time can stretch to 14 hours on average-sometimes as long as 24 hours. That’s more than six times longer. And when the drug lingers, so do its side effects.

What Happens When the Liver Fails

Liver disease-whether from alcohol, fat buildup, or hepatitis-slows down or blocks these metabolic pathways. In non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), CYP3A4 activity drops. In alcohol-related liver disease, CYP2E1 spikes, which can create toxic byproducts when combined with opioids. The result? Higher drug levels, slower clearance, and unpredictable reactions.

For morphine, the problem gets worse because its metabolites are active and toxic. In severe liver failure, morphine’s half-life can double or triple. Even if you take the same dose, your body can’t get rid of it fast enough. Studies show plasma clearance drops by up to 70% in cirrhosis. That’s not a small change-it’s a medical red flag.

Oxycodone isn’t safer. In patients with severe liver impairment, peak concentrations rise by 40%. That means the highest level of drug in the blood-where side effects like drowsiness and breathing trouble happen-is much higher than expected. And since the drug stays around longer, those effects last longer too.

Which Opioids Are Riskiest in Liver Disease?

Not all opioids are created equal when the liver is damaged. Some are far more dangerous than others.

- Morphine: High risk. Its reliance on glucuronidation makes it one of the worst choices in liver failure. Even small doses can lead to M3G buildup and neurotoxicity.

- Oxycodone: Also high risk. Dose reductions of 30% to 50% are needed in severe liver disease. Starting with a normal dose can be fatal.

- Methadone: Metabolized by multiple enzymes, so it’s theoretically less vulnerable-but there are no clear dosing rules for liver patients. This lack of guidance makes it unpredictable.

- Fentanyl and buprenorphine: These are transdermal or sublingual, so they avoid first-pass liver metabolism. That makes them safer options in theory, but research is still limited. No solid dosing guidelines exist yet.

Doctors often default to morphine because it’s cheap and familiar. But in liver disease, that’s like using a sledgehammer to fix a cracked windshield. The damage it causes may not show up right away-but it’s there.

How Opioids Can Worsen Liver Damage

It’s not just about how the liver handles opioids. Opioids can also hurt the liver directly. Chronic use changes the gut microbiome-the trillions of bacteria living in your intestines. These bacteria help regulate liver health through the gut-liver axis. When opioids disrupt that balance, harmful bacteria grow, leak into the bloodstream, and trigger liver inflammation.

This isn’t just theory. Studies in patients with cirrhosis who use opioids long-term show higher levels of liver enzymes and faster progression of fibrosis. The more opioids taken, the more the liver gets attacked-not just by the drug’s metabolites, but by the body’s own inflammatory response.

Dosing Adjustments That Actually Work

There’s no one-size-fits-all rule, but experts agree on some basic principles:

- Early liver disease: Reduce morphine doses by 25%-50%, but keep dosing intervals the same. Don’t wait longer between doses-your body still clears the drug slowly, so spacing won’t help if the dose is too high.

- Advanced liver failure: Cut doses by at least 50% and extend the time between doses. For oxycodone, start at 30%-50% of the usual dose. Monitor closely for drowsiness, confusion, or slow breathing.

- Never use extended-release opioids in liver disease. They release drug over hours, and if your liver can’t clear it, you’re building up a slow-burning overdose.

- Use the lowest effective dose for the shortest time possible. If pain can be managed with acetaminophen (in safe limits) or non-drug therapies, skip opioids entirely.

Many doctors still prescribe standard doses because they don’t know the data. But the evidence is clear: liver disease changes how opioids behave. Ignoring that is negligence.

What About Newer Opioids or Alternatives?

Transdermal fentanyl and buprenorphine patches avoid the liver’s first-pass effect, meaning less drug hits the liver upfront. That’s why they’re often recommended for patients with liver disease. But here’s the catch: there’s almost no large-scale data on how these drugs behave in advanced cirrhosis. We know they’re safer in theory, but we don’t know exact dosing. That’s a gap in care.

Non-opioid options like gabapentin, pregabalin, or even low-dose naltrexone (used off-label for pain and inflammation) are worth considering. Physical therapy, nerve blocks, and cognitive behavioral therapy for pain also reduce reliance on drugs that the liver can’t handle.

The Bottom Line

If you or someone you care for has liver disease and is on opioids, this isn’t just a routine prescription. It’s a ticking clock. The liver’s ability to process drugs declines gradually. By the time symptoms show up, it’s often too late. The safest approach isn’t to avoid pain treatment-it’s to choose the right drug, at the right dose, with the right monitoring.

Doctors need to stop assuming standard opioid doses are safe for liver patients. Patients need to speak up if they feel unusually drowsy, confused, or short of breath. And everyone needs to understand: in liver disease, opioids aren’t just less effective-they’re more dangerous. The numbers don’t lie. A 40% increase in drug concentration. A 14-hour half-life. A 70% drop in clearance. These aren’t abstract stats. They’re warning signs.

The goal isn’t to eliminate pain relief. It’s to deliver it safely. That means knowing how the liver works, how opioids change when it doesn’t, and choosing treatment based on science-not habit.

Can I still take morphine if I have cirrhosis?

Morphine is one of the riskiest opioids for people with cirrhosis. Its metabolites build up in the blood and can cause neurological toxicity, including seizures and confusion. If morphine must be used, the dose should be reduced by at least 50%, and dosing intervals should be extended. Even then, close monitoring is essential. Many experts recommend avoiding morphine entirely in advanced liver disease.

Is oxycodone safer than morphine for liver patients?

Neither is truly safe, but oxycodone has clearer dosing guidelines. In severe liver impairment, starting doses should be reduced to 30%-50% of normal. Unlike morphine, oxycodone doesn’t produce neurotoxic metabolites, so the risk profile is slightly better. But its half-life extends dramatically-from 3.5 hours to over 14 hours-so even small doses can accumulate. It’s a better option than morphine, but still requires extreme caution.

Why do opioids cause more side effects in liver disease?

The liver is responsible for breaking down and clearing opioids from the body. In liver disease, enzymes like CYP3A4 and glucuronosyltransferases work slower or not at all. This means opioids stay in the bloodstream longer and reach higher concentrations. The result? Increased drowsiness, slowed breathing, confusion, and even coma. Side effects aren’t just more common-they’re more severe and longer-lasting.

Can opioids make my liver disease worse?

Yes. Long-term opioid use disrupts the gut microbiome, leading to increased gut permeability and bacterial toxins entering the bloodstream. These toxins trigger inflammation in the liver, accelerating fibrosis and worsening conditions like NAFLD and cirrhosis. Studies show patients on chronic opioids have higher liver enzyme levels and faster disease progression than those not using opioids.

Are there any opioids that are safe for liver disease?

No opioid is completely safe, but transdermal fentanyl and buprenorphine patches are preferred because they bypass the liver’s first-pass metabolism. However, dosing guidelines are not well established, and research is limited. Even these options require careful monitoring. The safest strategy is to use non-opioid pain treatments whenever possible and reserve opioids for short-term, low-dose use under close supervision.

Skye Kooyman

January 26, 2026 AT 16:54Been watching my dad go through this with cirrhosis. They gave him oxycodone for back pain and he was zoning out for days. No one told us the dose needed to be cut in half. Scary stuff.

Karen Droege

January 27, 2026 AT 16:36This is the most vital public health thread I’ve read in years. The medical community’s blind spot here is criminal. Morphine in cirrhosis? It’s like giving a diabetic insulin without checking blood sugar. We’re not talking about rare side effects-we’re talking about predictable, preventable deaths. And yet, hospitals still default to it because it’s cheap and familiar. Shameful. We need mandatory liver-function dosing protocols. Now.

Kipper Pickens

January 28, 2026 AT 23:43From a pharmacokinetic standpoint, the CYP3A4 downregulation in NAFLD is well-documented, but the clinical translation remains inconsistent across institutions. The pharmacodynamic variability in opioid receptor sensitivity in hepatic encephalopathy further complicates dosing paradigms. We need randomized controlled trials with pharmacogenomic stratification, not just anecdotal dose reductions.

Neil Thorogood

January 29, 2026 AT 14:36So let me get this straight-we’re telling people with liver failure to avoid opioids… but also not to treat their pain? 😂 Classic medicine. Next you’ll tell me to ‘just breathe through the tumor’.

Dan Nichols

January 29, 2026 AT 23:16Anyone who says fentanyl is safe for liver patients is selling something. The patch doesn’t bypass metabolism-it just delays it. And when your liver finally gives out? Boom. Accumulation. You think the ER docs don’t see this every week? They do. They just don’t say it out loud.

Renia Pyles

January 30, 2026 AT 05:13Oh wow. Another ‘medical expert’ telling us what we can’t do. Meanwhile, my mom’s in agony and the doctors won’t touch anything stronger than Tylenol. So now we’re supposed to suffer because some guy in a lab coat doesn’t like morphine? Grow up.

Rakesh Kakkad

January 31, 2026 AT 02:16As someone from India where liver disease is rampant due to alcohol and hepatitis B, I can confirm that doctors here rarely adjust opioid doses. Many patients die quietly at home because no one told them the risks. This article should be mandatory reading for every medical student in South Asia.

Simran Kaur

February 1, 2026 AT 01:51My aunt had NAFLD and was on oxycodone for chronic pain. She started having hallucinations and couldn’t walk straight. We didn’t know it was the meds until her liver specialist pulled the plug. This saved her life. Thank you for putting this out there. So many people don’t know.

Peter Sharplin

February 1, 2026 AT 12:46I’ve worked in pain management for 18 years. The most common mistake? Assuming a 30% dose reduction is enough for advanced cirrhosis. It’s not. We’ve lost patients at 50% reductions because their clearance was down 80%. The rule of thumb? Start at 25% of normal, monitor for 72 hours, then titrate. And never, ever use extended release. Ever.

Faisal Mohamed

February 1, 2026 AT 20:20It’s ironic. We weaponize the liver’s vulnerability to justify opioid avoidance, yet we ignore the deeper truth: pain is a human right. When we pathologize suffering because of organ failure, we’re not practicing medicine-we’re practicing moral superiority. The body breaks. The soul aches. We must hold space for both.

eric fert

February 2, 2026 AT 19:30Let’s be real. This whole thing is just Big Pharma’s way of pushing buprenorphine patches. They know liver patients are a goldmine-long-term, high-margin, low-litigation. And now you’ve got doctors scared to prescribe anything else. Meanwhile, the real issue? No one’s funding non-opioid alternatives. This isn’t science. It’s a sales pitch wrapped in a white coat.

Allie Lehto

February 4, 2026 AT 04:51im so mad at doctors. they just give you the same pills they give everyone. my cousin died from this. no one told her. she was just told to ‘take it as needed’. how is that even legal???

Suresh Kumar Govindan

February 5, 2026 AT 17:46There’s a reason this isn’t widely taught. The pharmaceutical industry profits from standard dosing. If every liver patient got individualized opioid regimens, margins would collapse. This article isn’t about safety-it’s about exposing a trillion-dollar lie. Wake up.