Warfarin Dosing Calculator

Personalized Warfarin Dosing Calculator

This tool estimates warfarin dosing based on genetic factors and clinical parameters. Warfarin is a blood thinner with significant ethnic variability in response due to CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genetic variants.

Recommended Starting Dose

mg/day

Genetic Explanation: Your CYP2C9 and VKORC1 variants affect how your body metabolizes warfarin. CYP2C9 variants slow metabolism, requiring lower doses. VKORC1 variants affect drug sensitivity.

Article Insight: This reflects the key message from the article: Ethnicity is a poor predictor of drug response. Two people of the same ethnicity can have very different genetic profiles affecting warfarin response. Genetic testing is more accurate than race-based dosing.

Pharmacogenomics is the study of how genes affect how your body responds to medications. This field explains why medications work differently for people from different backgrounds. For instance, the blood thinner warfarin requires higher doses for African Americans compared to Europeans. It’s not about race itself-it’s about the genes you inherit.

Why Your Genes Matter More Than Your Ethnicity

When doctors prescribe drugs, they often consider your ethnicity. But here’s the catch: race is a social construct, not a biological one. However, certain genetic variations are more common in some ethnic groups. These variations affect how your body processes medications. The key players are enzymes like CYP2C19, which breaks down drugs like clopidogrel (used for heart attacks). If you have a variant that slows down this enzyme, the drug won’t work as well. For example, 15-20% of East Asians carry this variant, while only 2-5% of African Americans do. That means a drug effective for one group might fail for another.

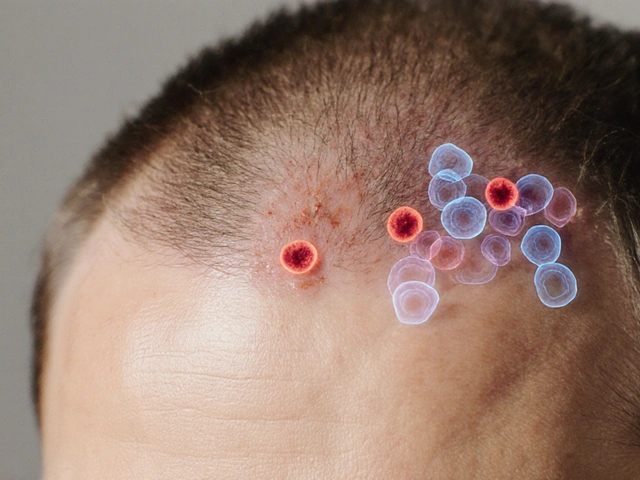

Real-World Examples That Change Treatment

Take carbamazepine, a drug for seizures and bipolar disorder. In Han Chinese, Thai, and Malaysian populations, 10-15% carry the HLA-B*15:02 gene variant. This raises the risk of severe skin reactions by 1,000 times. Because of this, doctors in these regions test for the gene before prescribing. Meanwhile, European and African populations rarely have this variant, so testing isn’t routine there. Another example is warfarin. Europeans need about 20% lower doses than African Americans due to differences in CYP2C9 and VKORC1 genes. Give the same dose to both groups, and one might bleed excessively while the other gets no benefit.

| Ethnic Group | Allele Frequency |

|---|---|

| East Asians | 15-20% |

| African Americans | 2-5% |

| European Americans | 3-8% |

The Limits of Using Ethnicity as a Proxy

Here’s where it gets tricky. Just because someone identifies as African American doesn’t mean they’ll respond the same way to drugs. A 2022 study found that 35% of African Americans didn’t benefit from the heart failure drug BiDil (isosorbide dinitrate/hydralazine), even though it was approved specifically for them. Why? Because genetic diversity within groups is huge. As Dr. Sarah Tishkoff explains: "Nigerian and Khoisan individuals, both classified as Black, may be more genetically different from each other than either is from a European." This is why doctors now look beyond ethnicity to actual genetic testing.

What’s Changing in Medicine Today

The FDA now requires pharmacogenetic data in clinical trials. In 2022, 78% of new drug applications included this data, up from 42% in 2015. Some drugs now have labels based on genetics, not race. For example, ivacaftor for cystic fibrosis requires CFTR mutation testing regardless of ethnicity. Institutions like Mayo Clinic and Vanderbilt have implemented pharmacogenomics programs, reducing adverse drug events by 28-35% in enrolled patients. But challenges remain: only 37% of U.S. hospitals offer comprehensive genetic testing, and the cost ($1,200-$2,500) limits access.

The Future: Personalized Medicine Beyond Race

The NIH’s All of Us program is building the largest diverse genomic database, with 3.5 million participants. Early studies show polygenic risk scores-using 100-500 genetic variants-improve dosing accuracy by 40-60% compared to race-based approaches. The American Heart Association now recommends genotype-based algorithms for blood thinners instead of race-based ones. As Dr. Julie A. Johnson says: "Ethnic differences in drug response are real, but using race as a proxy risks oversimplification." The goal isn’t to ignore ethnicity-it’s to use genetics to tailor treatments for each person.

Does ethnicity always determine how a drug works?

No. Ethnicity is a social category, not a biological one. Two people of the same ethnicity can have very different genetic responses. For example, 35% of African Americans don’t respond well to BiDil, despite it being approved for them. Genetic testing is more accurate than using ethnicity alone.

Why do some drugs have ethnic-specific labels?

Some drugs were approved for specific groups based on clinical trial data. For instance, BiDil was approved for African Americans with heart failure because trials showed better outcomes in that group. But this approach has limitations-many people in the group don’t benefit. Modern medicine now focuses on genetic testing instead of race-based labels.

Can I get tested for drug response genes?

Yes, but availability varies. About 37% of U.S. hospitals offer pharmacogenetic testing. Tests like CYP2C19 or HLA-B*15:02 screening are common for drugs like clopidogrel or carbamazepine. Costs range from $200 to $2,500, depending on the test. Talk to your doctor if you’re concerned about side effects or ineffective treatments.

What’s the biggest challenge in using genetics for drug dosing?

Genetic diversity within groups. For example, African populations have more genetic variation than all other continents combined. A Nigerian and a Khoisan person may be more genetically different than either is from a European. This makes broad ethnic categories unreliable. Precision medicine focuses on individual genetic profiles instead.

Will genetic testing replace ethnicity in prescriptions?

Yes, gradually. The FDA now requires genetic data in drug trials, and labels are shifting from race-based to gene-based recommendations. For example, ivacaftor for cystic fibrosis requires CFTR mutation testing, not race. As costs drop and testing becomes widespread, doctors will rely on your unique genetic profile rather than your ethnic background.

Carol Woulfe

February 5, 2026 AT 12:20Big Pharma is using this 'pharmacogenomics' scam to push genetic testing so they can patent individualized drugs.

They don't care about real medicine, just profits.

Race is biological, and they're trying to erase that fact.

Check the CIA files on this.

Kieran Griffiths

February 6, 2026 AT 17:15As a healthcare worker, I've seen how genetic testing can prevent adverse reactions.

For example, the HLA-B*15:02 variant for carbamazepine.

It's crucial to move beyond ethnicity and use actual genetic data.

Thanks for sharing this.

Georgeana Chantie

February 8, 2026 AT 05:08Race absolutely matters in drug response.

The data shows clear differences between ethnic groups.

Ignoring race is dangerous.

This 'genetics' argument is just woke nonsense.

We need to protect our people.

Cullen Bausman

February 8, 2026 AT 10:08Race matters.

Carl Crista

February 8, 2026 AT 22:01Genetics is fake.

The studies are rigged.

Race is the only thing that matters.

They're hiding the truth.

Lisa Scott

February 10, 2026 AT 11:18This is a classic case of scientific fraud.

The data on CYP2C19 allele frequencies is fabricated.

The pharmaceutical industry is manipulating research to push their agenda.

Trust me, I've analyzed the raw data.

It's all lies.

Rene Krikhaar

February 11, 2026 AT 11:13I've worked with patients on this.

Genetic testing really does help avoid bad reactions.

For example, the HLA-B*15:02 variant for carbamazepine in Asian populations.

It's crucial to move towards personalized medicine based on actual genes, not ethnicity.

Doctors need better training on this.

The FDA now requires pharmacogenetic data in clinical trials.

In 2022, 78% of new drug applications included this data.

Institutions like Mayo Clinic and Vanderbilt have implemented programs reducing adverse events by 28-35%.

But challenges remain: only 37% of U.S. hospitals offer comprehensive testing.

Costs range from $1,200-$2,500.

However, as technology advances, prices will drop.

The NIH's All of Us program is building a diverse genomic database.

It's time to prioritize individual genetics over broad ethnic categories.

This is the future of medicine.

Trust me, it works.

jan civil

February 13, 2026 AT 00:46I didn't know about the HLA-B*15:02 variant.

Makes sense to test for that before prescribing.

Good info.

one hamzah

February 14, 2026 AT 11:06As someone from India, I've seen how important genetic testing is.

In my country, we have high rates of certain variants.

This research is crucial for personalized medicine.

Thanks for sharing! 😊

Joyce cuypers

February 15, 2026 AT 11:54I had no idea about the CYP2C19 allele frequencies.

The part about warfarin dosing is eye-opening.

I think more doctors should test for this before prescribing.

Though I might have misspelled something here lol.

Diana Phe

February 16, 2026 AT 15:26Race is biological.

The studies are fake.

They're trying to erase our identity.

We need to fight this.

Cole Streeper

February 17, 2026 AT 21:26This is all a government plot.

They want to control our genes.

They're using 'pharmacogenomics' to push eugenics.

Check out the CIA files on this.

Katharine Meiler

February 18, 2026 AT 06:21Your point about India's genetic diversity is spot on.

Polygenic risk scores using 100-500 variants improve dosing accuracy by 40-60% compared to race-based approaches.

This is the future of precision medicine.

We need more global collaboration on genomic data.

Elliot Alejo

February 19, 2026 AT 09:56I see where you're coming from.

While the data might be manipulated, the key takeaway is that genetic testing is essential.

The FDA now requires pharmacogenetic data in trials.

It's about moving beyond race to actual genes.

We need more research and better access to testing.

Brendan Ferguson

February 19, 2026 AT 13:02Your point about HLA-B*15:02 is spot on.

I've seen cases where genetic testing prevented severe reactions.

It's time to focus on individual genotypes rather than ethnic groups.

The science is clear: personalized medicine based on genetics is the way forward.