Key Takeaways

- Hair loss can be a direct symptom of several autoimmune diseases.

- Alopecia areata is the classic autoimmune‑driven hair loss, but lupus, thyroid disorders, celiac disease, psoriasis, vitiligo, rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn’s disease can also affect the scalp and body hair.

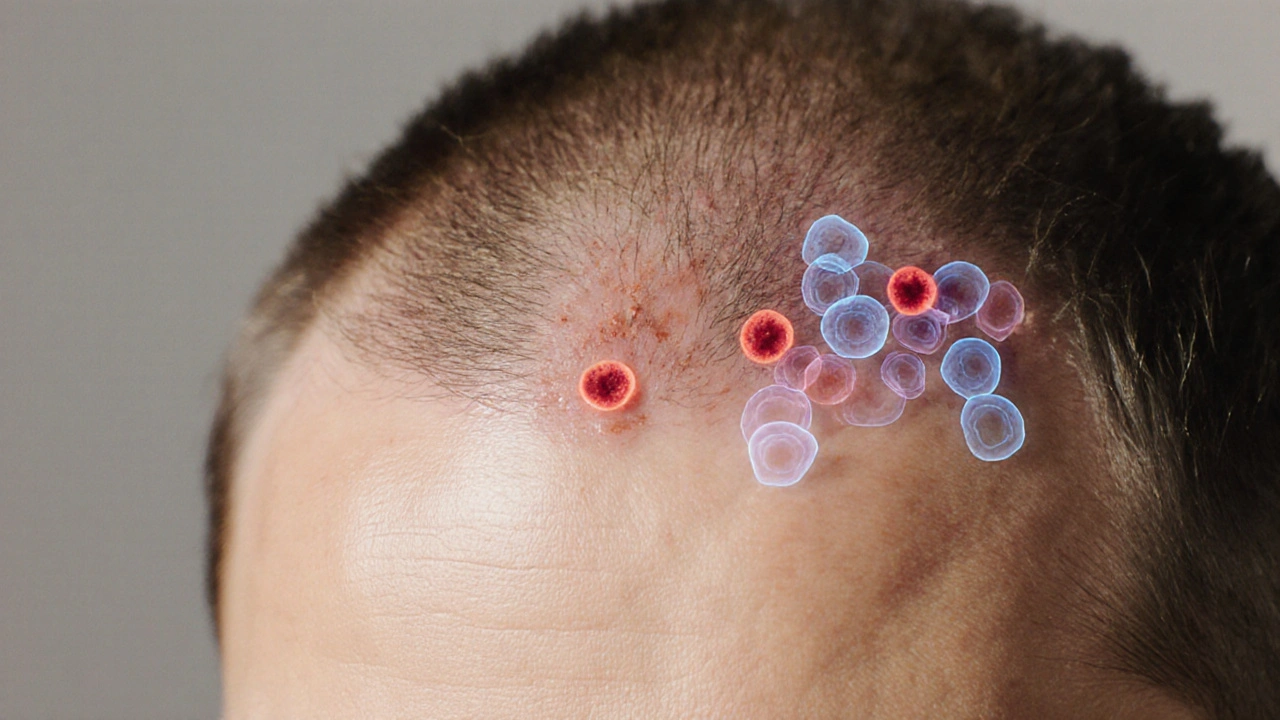

- The immune system attacks hair follicles by mistaking them for foreign invaders, leading to inflammation and shedding.

- Early diagnosis, blood work, and a scalp examination help differentiate autoimmune hair loss from other causes.

- Treatment combines medication, stress management, nutrition and gentle hair‑care practices.

When you notice a patch of missing hair, you might wonder whether it’s just genetics, stress, or something more serious. autoimmune hair loss is a real medical pattern where the body’s own defense system turns against the hair follicles. Understanding the link can save you months of frustration and help you get the right care faster.

What is Hair Loss?

Hair loss is the partial or complete shedding of hair from the scalp or body. It can be temporary (telogen effluvium) or permanent (scarring alopecia). While hormones, nutrition and aging play roles, the immune system is the hidden culprit in many stubborn cases.

How Autoimmune Diseases Attack Your Hair

Autoimmune disease autoimmune disease occurs when immune cells-especially T‑cells and antibodies-mistake healthy tissue for a threat. In the scalp, this misrecognition triggers inflammation around the hair follicle, cutting off the blood supply and halting the growth cycle. The result is sudden shedding, patchy bald spots, or a dry, flaky scalp that looks like dandruff.

Autoimmune Conditions Commonly Linked to Hair Loss

Below are the most frequently reported diseases that can cause hair loss, each with a brief description of how it shows up on the head.

- Alopecia areata: A rapid‑onset, patchy loss where the immune system targets hair follicles. Affects 2% of the population and can progress to total scalp (alopecia totalis) or whole‑body loss (alopecia universalis).

- Lupus erythematosus (systemic or discoid): Causes scarring alopecia, often with a reddish‑purple rash. The inflammation can damage follicles permanently if not treated.

- Hashimoto thyroiditis: An autoimmune attack on the thyroid gland that leads to hypothyroidism. Low thyroid hormone slows the hair‑growth cycle, resulting in diffuse thinning.

- Celiac disease: Gluten‑triggered intestinal autoimmunity can cause nutrient malabsorption and a scalp‑wide shedding known as telogen effluvium.

- Psoriasis: The skin‑focused autoimmune disease often involves the scalp, leading to thick, silvery plaques that trap hair shafts and cause breakage.

- Vitiligo: While primarily a pigment disorder, the autoimmune process can co‑occur with alopecia areata, producing white‑spotted hair loss patches.

- Rheumatoid arthritis: Chronic systemic inflammation can indirectly trigger telogen effluvium, especially during flare‑ups.

- Crohn’s disease (inflammatory bowel disease): Nutrient deficiencies and systemic inflammation often lead to diffuse thinning.

Comparing Autoimmune Diseases and Their Hair‑Loss Patterns

| Autoimmune Disease | Hair‑Loss Pattern | Approx. Frequency of Hair Loss | Key Treatment Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alopecia areata | Patchy, round spots | ~100% (by definition) | Topical/Intralesional steroids, JAK inhibitors |

| Lupus erythematosus | Scarring, irregular patches | 10‑20% | Systemic antimalarials, steroids |

| Hashimoto thyroiditis | Diffuse thinning | 30‑50% | Levothyroxine replacement |

| Celiac disease | Telogen effluvium (diffuse shedding) | 5‑15% | Gluten‑free diet, nutritional supplements |

| Psoriasis | Scalp plaques causing breakage | 8‑12% | Topical steroids, vitamin D analogues |

| Vitiligo | Co‑occurs with alopecia areata patches | ~5% | Topical steroids, calcineurin inhibitors |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Telogen effluvium during flares | 3‑10% | DMARDs, biologics |

| Crohn’s disease | Diffuse thinning, sometimes patchy | 4‑12% | Anti‑inflammatories, nutrient repletion |

When to Seek Medical Help

Because many autoimmune conditions share systemic symptoms, a dermatologist or rheumatologist will usually run a set of baseline tests:

- Complete blood count (CBC) and inflammatory markers (ESR, CRP).

- Autoantibody panel: ANA, anti‑dsDNA, anti‑thyroid peroxidase (TPO), anti‑gliadin, anti‑tissue transglutaminase.

- Thyroid function test (TSH, free T4).

- Scalp biopsy if scarring alopecia is suspected.

If you notice sudden patchy bald spots, an itchy or painful rash, or overall thinning that coincides with fatigue, joint pain, or digestive issues, book an appointment promptly. Early treatment often prevents permanent follicle damage.

Treatment Options Tailored to Autoimmune Hair Loss

Therapies fall into three buckets: immune modulation, symptom relief, and supportive care.

- Immune‑modulating drugs: Corticosteroids (topical, oral, intralesional) calm inflammation. Newer oral Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors (tofacitinib, ruxolitinib) show promise for alopecia areata and lupus‑related alopecia.

- Targeted disease treatment: For thyroid disease, levothyroxine restores hormone balance. A gluten‑free diet is the cornerstone for celiac‑related shedding. Biologics (TNF‑α blockers, IL‑6 inhibitors) help rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn’s disease, indirectly reducing hair loss.

- Supportive care: Gentle shampoos, silicone‑based scalp protectors, and avoiding tight hairstyles reduce mechanical breakage. Nutrient supplementation-iron, zinc, vitaminD, biotin-fills gaps created by malabsorption.

Lifestyle Strategies to Reduce Autoimmune Hair Loss

Even with medication, lifestyle choices can tip the balance toward regrowth.

- Stress management: Chronic cortisol spikes aggravate autoimmunity. Try mindfulness meditation, short daily walks, or yoga.

- Balanced diet: Focus on anti‑inflammatory foods-fatty fish (omega‑3), leafy greens, berries, and fermented foods. Limit processed sugars and dairy if they trigger flare‑ups.

- Sleep hygiene: Aim for 7‑8hours of deep sleep; it supports hormone regulation and immune recovery.

- Hair‑care routine: Use sulfate‑free, pH‑balanced shampoos; avoid daily heat styling; let hair air‑dry when possible.

- Regular medical follow‑up: Track lab results every 3‑6months to adjust therapy before hair loss worsens.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can stress alone cause autoimmune hair loss?

Stress doesn’t cause autoimmunity, but it can flare an existing condition. High cortisol levels disrupt the hair‑growth cycle and may trigger a sudden shedding episode in people already predisposed.

Is alopecia areata always an autoimmune disease?

Yes. Alopecia areata is defined by an autoimmune attack on the hair follicle. Even when it appears isolated, blood tests often reveal subtle autoantibodies.

Will treating my thyroid condition fix my hair loss?

Correcting thyroid hormone levels usually improves diffuse thinning within 3‑6months. However, if hair follicles have been dormant for a long time, regrowth may be slower.

Are there any natural remedies that work for autoimmune hair loss?

Topical pumpkin‑seed oil, rosemary essential oil, and oral saw‑palmetto have modest evidence for reducing inflammation, but they should complement- not replace-medical therapy.

Can I still get a hair transplant if I have an autoimmune disease?

A transplant is possible once the autoimmune condition is well‑controlled (no active flare). Surgeons usually require stable labs for at least 6months before proceeding.

Understanding the connection between hair loss and autoimmunity empowers you to ask the right questions, get accurate testing, and start a treatment plan that targets the root cause-not just the visible symptom.

Richard Walker

October 12, 2025 AT 14:57Interesting overview of how the immune system can go rogue on our hair follicles. It’s surprising how many common autoimmune disorders have hair loss as a side effect. I’ve seen a few friends with Hashimoto’s suddenly notice thinning strands, and they never connected the dots until reading something like this. The way you broke down each disease makes it easier for non‑medical folks to spot patterns. Overall, a solid primer for anyone noticing unexpected shedding.

Julien Martin

October 16, 2025 AT 17:34Great stuff, very helpful.

Jason Oeltjen

October 20, 2025 AT 18:47I gotta say, this article does a good job but it also kinda glosses over the real moral issue – people keep accepting autoimmune diagnoses without questioning pharma motives. The way they push JAK inhibitors feels like a cash grab, and most patients don’t get the full picture. Also, the grammar could use a polish – there are a few stray commas that make the sentences wobble.

Mark Vondrasek

October 24, 2025 AT 20:00Wow, Jason, you really think it’s a cash‑grab? That’s a classic conspiracy line. While it’s true pharma profits matter, dismissing all meds as evil doesn’t help anyone battling real hair loss. People with alopecia areata need evidence‑based options, and JAK inhibitors have solid trial data. Plus, the article actually mentions lifestyle tweaks alongside meds – it’s not a one‑size‑fits‑all pitch. Let’s keep the sarcasm in check and focus on what works.

Joshua Agabu

October 28, 2025 AT 20:14The piece does a good job tying thyroid issues to diffuse thinning. Low thyroid hormone really slows the hair cycle, and a simple blood test can catch it early. It’s also worth noting that iron deficiency, even without celiac, can exacerbate shedding. Keeping an eye on basic labs can spare a lot of frustration.

Amy Robbins

November 1, 2025 AT 21:27Sure, basic labs are nice, but most people just Google “why am I losing hair” and end up buying supplements from sketchy sites. Your suggestion to get a CBC is fine, but it’s also a sneaky way to push more medical appointments – more bills, more prescriptions. And let’s not forget, diet changes are rarely as simple as “just go gluten‑free”.

Brian Johnson

November 5, 2025 AT 22:40I appreciate the balanced tone of the article. It’s reassuring to see both medical and lifestyle strategies side by side. For those dealing with stress‑triggered flares, incorporating mindfulness can really complement the pharmacologic approach. Thanks for covering the whole picture.

Jessica Haggard

November 9, 2025 AT 23:54Brian, exactly – a holistic view is what patients need. It’s not just about slapping on steroids; it’s about stabilising the whole system. I’d add that regular follow‑ups every few months can catch early signs before the hair loss becomes irreversible. Keep advocating for that comprehensive care!

Mary Magdalen

November 14, 2025 AT 01:07Whoa, the autoimmune‑hair‑loss connection feels like a secret garden of hidden culprits. Imagine the hair follicles as tiny soldiers, and suddenly a rogue commander (your thyroid or gut) sends them into battle. It’s poetic, albeit a bit tragic, how our bodies can turn against something as innocent as a strand of hair. Really makes you think about the delicate balance inside us.

Dhakad rahul

November 18, 2025 AT 02:20Ah, the poetic soldier metaphor! It reminds me of Shakespearean tragedy where the protagonist’s own mind betrays them. Though, let’s not get lost in melodrama – real‑world solutions matter more than lyrical musings. Still, I love the drama of science meeting storytelling!

William Dizon

November 22, 2025 AT 03:34When it comes to autoimmune‑induced hair loss, the first step is always a thorough clinical assessment. A dermatologist will typically start with a detailed scalp examination, looking for characteristic patterns like the round patches of alopecia areata or the scarring signs of lupus‑related alopecia. From there, lab work is essential: a complete blood count (CBC) can reveal anemia or infection, while inflammatory markers such as ESR and CRP give a snapshot of systemic activity. Autoantibody panels are the next logical piece – ANA, anti‑dsDNA, anti‑TPO, anti‑tTG, and others can pinpoint specific conditions like systemic lupus, Hashimoto thyroiditis, or celiac disease. Thyroid function tests (TSH and free T4) are particularly important because even subclinical hypothyroidism can cause diffuse thinning that mimics other forms of alopecia. If scarring alopecia is suspected, a scalp biopsy can provide definitive histologic evidence of follicular destruction, guiding therapeutic decisions. Treatment plans should be individualized: topical or intralesional corticosteroids remain first‑line for many localized patches, while systemic immunomodulators (such as oral corticosteroids or newer JAK inhibitors) are reserved for extensive disease or when topical therapy fails. Addressing the underlying autoimmune disease is crucial – levothyroxine for hypothyroidism, a strict gluten‑free diet for celiac‑related shedding, and disease‑modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) or biologics for rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn’s disease can dramatically reduce inflammation and halt hair loss progression. Nutritional support should not be overlooked; deficiencies in iron, zinc, vitamin D, and biotin are common in these patients and supplementation can improve hair follicle health. Lifestyle modifications, including stress management techniques like mindfulness meditation, regular exercise, and adequate sleep, further support the immune system and promote regrowth. Finally, regular follow‑up every three to six months allows clinicians to monitor lab parameters, adjust therapies, and ensure that any emerging side effects are addressed promptly. By integrating precise diagnostics with targeted medical and supportive therapies, patients have a realistic chance of halting or even reversing autoimmune‑related hair loss.

Jenae Bauer

November 26, 2025 AT 04:47William, your deep‑dive reads like a textbook, but it’s exactly what the layperson needs to demystify the process. The step‑by‑step lab ordering feels almost philosophical – an ordered quest for hidden truths in our bodies. It reminds me how knowledge itself can be a form of therapy.

Ira Bliss

November 30, 2025 AT 06:00Love the thoroughness! 🌟 This really motivated me to book an appointment and get those labs done. Thanks for the clear roadmap! 😊

Donny Bryant

December 4, 2025 AT 07:14Nice work. The article keeps it simple enough for people without a medical background while still covering the essential tests and treatments. It’s good to see an emphasis on both medication and lifestyle.

kuldeep jangra

December 8, 2025 AT 08:27As a coach, I always tell my clients that understanding the root cause is half the battle. This piece does a commendable job of laying out the cascade from immune misrecognition to follicular fallout, which can help demystify the experience for many. It’s also reassuring to see the emphasis on supportive measures – everything from diet to stress reduction has a place in the recovery plan. When you combine medical interventions with consistent, gentle hair‑care habits, you create an environment where follicles can regain confidence, so to speak. I’ll definitely be sharing this with the group I work with, especially those wrestling with unexplained thinning.

harry wheeler

December 12, 2025 AT 09:40Good summary, clear and concise. Helpful for anyone looking for a quick overview.

faith long

December 16, 2025 AT 10:54I appreciate the balanced tone, but let’s not sugarcoat the frustration many feel when their hair starts falling out. The emotional toll is real – it can affect self‑esteem and social interactions. While the article offers solid medical advice, it could dig deeper into the psychological support options, such as counseling or support groups. Moreover, the suggestion to “avoid tight hairstyles” feels a bit simplistic when the underlying autoimmune trigger remains unaddressed. It’s crucial to empower patients with both medical and emotional tools to fight this battle.

Mauricio Banvard

December 20, 2025 AT 12:07Honestly, this whole autoimmune narrative is another layer of control – think about how pharma thrives on chronic conditions that never truly get “cured”. They push JAK inhibitors, claim breakthroughs, yet the side‑effects are downplayed. Meanwhile, natural anti‑inflammatory pathways are ignored. It’s a classic playbook, but I guess the article tries to stay neutral.

Michael GOUFIER

December 23, 2025 AT 13:57In conclusion, the intricate interplay between autoimmune mechanisms and hair follicle dynamics necessitates a multidisciplinary approach. Rigorous diagnostic evaluation, targeted pharmacotherapy, and adjunctive lifestyle modifications collectively foster optimal outcomes. Practitioners should remain vigilant for evolving therapeutic modalities, ensuring evidence‑based integration into patient care. Continued research will undoubtedly elucidate further pathways, enhancing our capacity to mitigate hair loss associated with autoimmunity. Thank you for a comprehensive and enlightening exposition.